Physiological-Based Cord Clamping

During birth a baby transitions from relying on the natural support in the womb of the mother, into breathing and living on its own strength.

A process involving major physiological changes in the newborn baby.

This animation explains what happens with the baby’s heart and blood-flow during this transition and how the timing of clamping the umbilical cord is of critical importance to the baby’s health.

Physiology

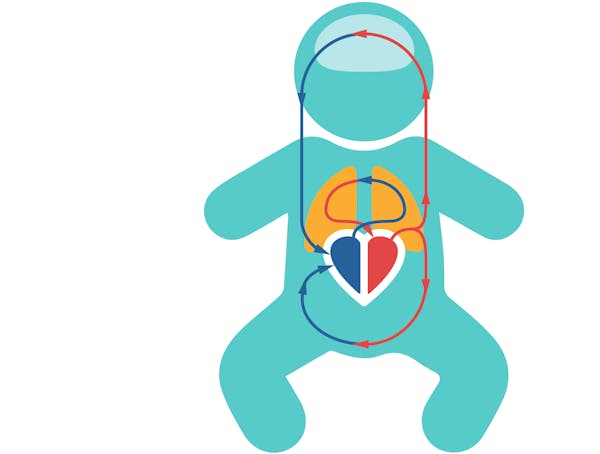

Before a baby is born, when it is still a fetus safely in the womb of its mother, it receives oxygen-rich blood from the placenta via the umbilical cord. During birth, the baby transitions from the support of the placenta to autonomous breathing and circulation, a magical process involving major circulatory and hemodynamic changes.

Newborn and adult circulation

In babies and adults, all the blood flows from the right side of the heart through the lungs, to be oxygenated, back to the left side of the heart. The left side then pumps the oxygenated blood into the body, to provide oxygen and nutrients to our cells. De-oxygenated blood then returns back into the right side of the heart.

Fetal circulation

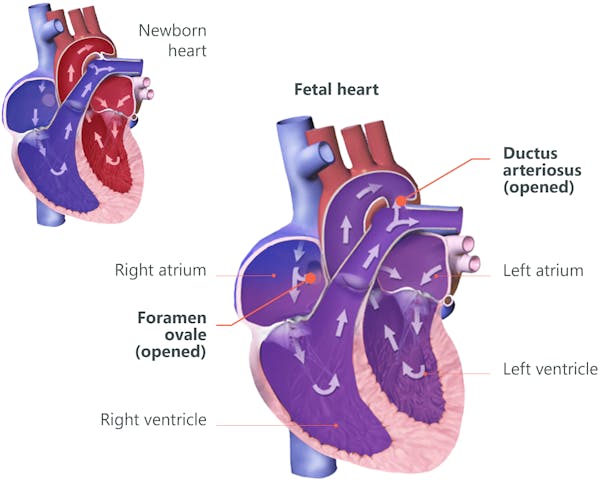

Fetal circulation is different to the circulation of a newborn baby and an adult. In the fetus, not much blood passes through the lungs. The fetus is not breathing air and the lungs are filled with fluids. Rather, it receives oxygen-rich blood from the placenta via the umbilical cord.

In fetal circulation, the placenta mainly supplies blood to the left atrium, through an anatomical opening called the foramen ovale.

Aside for the patent foramen ovale, there is another important connection, the patent ductus arteriosus, the connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta, allowing blood to travel through the pulmonary artery to bypass the lungs and go straight into the aorta. Blood can bypass the lungs because of high vascular resistance in the pulmonary arteries, allowing the blood to more easily flow into the aorta.

In the fetus, oxygenated blood flows through the umbilical vein to the liver and passes through the ductus venosus before joining with the inferior vena cava. The blood will enter the right atrium and then either go into the right ventricle or it will go through the patent foramen ovale into the left atrium, before being pumped in the left ventricle and into the (ascending) aorta. The blood that is pumped from the right ventricle can go through the pulmonary artery to enter the lungs, but mainly bypasses the lungs straight into the (descending) aorta via the patent ductus arteriosus. Through the aorta, blood flows into the fetal body and back to the placenta via the umbilical arteries.

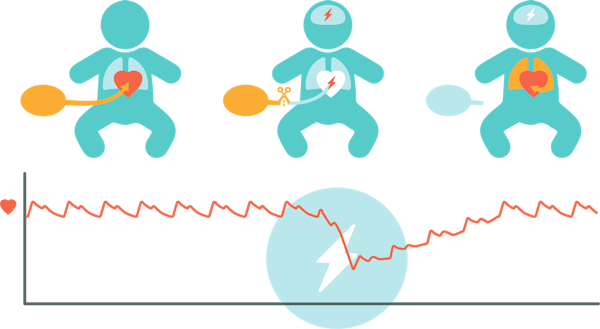

Early cord clamping^3-5^

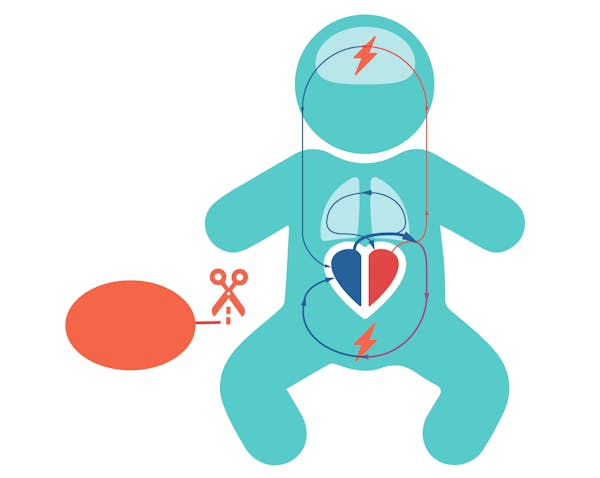

Around 1 in 10 babies do not breathe (sufficiently) at birth. Around the world, this affects over 35,000 newborns every day. Todays medical convention prescribes to cut the umbilical cord soon after birth, in order to provide urgent care. The placental circulation is cut off before the baby’s lungs are filled with air.

Clamping the umbilical cord before the baby aerates it's lungs can be harmful.

The first problem of clamping the umbilical cord so soon, is that blood, that was returning from the baby back into the placenta, is now all redirected through the baby’s body. Systemic vascular resistance increases and as a result, there is a very rapid increase in arterial pressure. This increases by at least 30% in only 4 heartbeats.

Secondly, the left side of the heart is deprived of venous return or preload. The blood-flow from the placenta into the heart is cut off while at the same time the pulmonary blood-flow remains low. The baby’s heart has less blood to pump, its heart rate will drop and cardiac output greatly decreases by up to 50% in only 60 seconds, thereby reducing the supply of vital oxygen to the baby’s organs, especially the brains.

The rapid increase in blood-pressure and the reduced oxygen supply to the organs, can cause injury, especially to the baby’s brains and intestines.

A recent meta-analyses in preterm infants found that early cord clamping in premature babies significantly increases the risk of death.^5^

Only after the baby’s lungs fill with air, redirecting the blood-flow through the lungs, the left atrium will be supplied with sufficient blood, to restore cardiac output.

Placental transfusion and circulation^6^

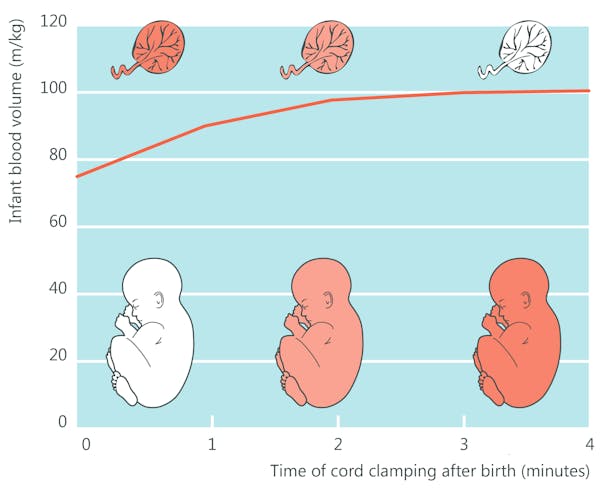

By keeping the umbilical cord intact, placental circulation and blood-flow from and to the baby is maintained for some minutes after birth. This blood is re-distributed to the baby’s organs, gradually transfusing blood volume from the placenta to the baby, delivering oxygen and important nutrients like iron.

In term neonates, the blood-flow from the placenta contributes to an additional 80-100ml circulating blood volume. This adds around 30% circulating blood-volume, including around 20-30mg/kg iron.

Research shows that gravity has little to no effect on placental transfusion and circulation. The main driver for placental circulation is the baby’s breathing, causing a pressure difference that “pulls” blood into its own circulation.

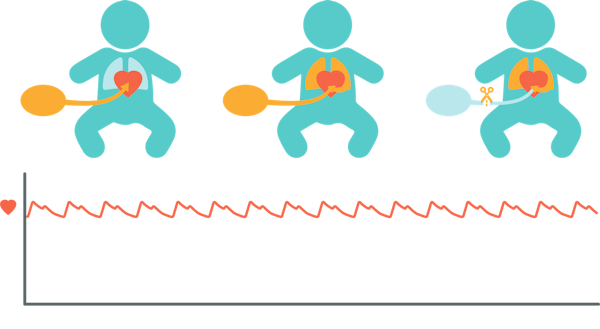

Physiological-based cord clamping

Physiological-based cord clamping means waiting with clamping the umbilical cord at a time until after the baby has aerated it's lungs, started breathing and has completed its physiological transition. The timing of cord clamping is guided by the baby’s own condition, instead of a fixed time.

Allowing the baby to aerate its lungs before clamping the cord, leads to a gentle switch from the oxygen-rich blood-flow from the placenta to autonomous breathing and blood flow. This prevents a rapid increase in blood-pressure and sustains heart rate and cardiac output and thus the supply of vital oxygen to the baby’s organs.

Intact cord stabilization

Around 1 in 10 babies do not breathe (sufficiently) at birth. These babies need respiratory support immediately after birth. To offer these babies the benefits of physiological-based cord clamping, respiratory support can be provided while keeping the umbilical cord intact.

The baby’s vital signs are used to determine when the cord can be clamped:

- Heart Rate > 100 bpm

- SpO2 > 85%

- FiO2 < 40%

- Preferably spontaneous breathing on nCPAP

Clinical evidence

Animal experimental research^3,4^

Studies in preterm lambs, comparing cord clamping before and after the onset of ventilation, have demonstrated, that clamping the cord after the initiation of ventilation, maintains cardiac output and prevents large fluctuations in systemic and cerebral blood pressures and flows.

These studies show that the haemodynamic changes, that occur during the transition period immediately after birth, are closely related to lung aeration and pulmonary perfusion.

Benefits for late preterm and term newborns^7-9^

An estimated one million newborns worldwide suffer from perinatal asphyxia. This group of baby's/ births include:

- Small for gestational age (SGA), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), maternal diabetes and rh-isoimmunization.

- Births involving fetal distress, shoulder dystocia, tight nuchal cords, or occult cords.

These babies are at risk of developing hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) due to inadequate blood-flow and oxygen delivery to the brain and other vital organs.

PBCC provides placental circulation, oxygenation and blood volume transfer. Proven benefits for newborns ≥34 wks G.A. include:

- Increased hemoglobin and hematocrit.

- Improved iron status in infancy, reducing (iron-deficiency) anemia in early infancy.

- Improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in early childhood.

Benefits for preterm newborns^5,10,12,18^

Many preterm babies need more time to start breathing after birth. Delaying cord clamping allows for more time for the baby’s lungs to aerate and ensures a smoother transition until the baby starts breathing on its own.

A recent network meta-analysis shows that preterm babies of all gestational ages benefit from the continued oxygen-rich blood-flow from the placenta.^5^ Results show that delaying cord clamping by more than 2 minutes can reduce the risk of death in premature babies by 70%.

Proven benefits in preterm newborns <34 wks G.A. include:

- Increased hemoglobin and hematocrit.

- Reduced number of blood transfusions.

- Reduced mortality.

- Reduced risk of late onset sepsis.

- Potentially improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in early childhood.

Benefits of stabilization with intact cord^11-18^

A number of clinical studies, with a time-based approach of waiting 60-120 sec with clamping the cord while providing respiratory support, have shown that this approach is feasible and safe for mother and baby.

Recently, a large multicenter RCT was published, called ABC3, using criteria for cord clamping based on the baby’s clinical condition.

Next to the listed benefits, the ABC3 trial shows that physiological-based cord clamping and intact cord stabilization or resuscitation:

- is safe for mother and baby

- results in a more stable cardiopulmonary transition, with a shorter time to stabilize

- improves survival without major complications

- centers with more experience achieve better results

- allows for immediate bonding between baby and mom

- is what parents prefer, parents were less anxious and more content

Birth can be improved

Literature references

- Healthy Newborn Network

- WHO fact sheet

- Bhatt S, Alison BJ, Wallace EM, Crossley KJ, Gill AW, Kluckow M, et al. Delaying cord clamping until ventilation onset improves cardiovascular function at birth in preterm lambs. J Physiol 2013 Apr 15;591(Pt 8): 2113-26. link

- Polglase GR, Dawson JA, Kluckow M, Gill AW, Davis PG, te Pas AB, et al. Ventilation onset prior to umbilical cord clamping (physiological-based cord clamping) improves systemic and cerebral oxygenation in preterm lambs. PLoS One 2015;10(2): e0117504. link

- Seidler AL, Libesman S, Hunter KE, Barba A, Aberoumand M, Williams JG, Shrestha N, Aagerup J, Sotiropoulos JX, Montgomery AA, Gyte GML, Duley L, Askie LM and iCOMP Collaborators. Short, medium, and long deferral of umbilical cord clamping compared with umbilical cord milking and immediate clamping at preterm birth: a systematic review and network meta-analysis with individual participant data. The Lancet Published Online November 14, 2023. link

- Yao AC, Moinian M, Lind J. Distribution of blood between infant and placenta after Birth. The Lancet 1969 Oct 25. link

- Ola Andersson, Nisha Rana, Uwe Ewald, Mats Målqvist, Gunilla Stripple, Omkar Basnet, Kalpana Subedi and Ashish KC. Intact cord resuscitation versus early cord clamping in the treatment of depressed newborn infants during the first 10 minutes of birth (Nepcord III)–a randomized clinical trial. Maternal Health, Neonatology, and Perinatology 2019(5:15). link

- Isacson M, Gurung R, Basnet O, Andersson O, Kc A. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of a randomised trial of intact cord resuscitation. Acta Paediatr. 2021 Feb;110(2):465-472. link

- Ola Andersson, Judith S. Mercer. Cord Management of the Term Newborn. Clinics in Perinatology, Volume 48, Issue 3, August 2021, Pages 447-470. link

- Rabe H, Gyte GM, Díaz-Rossello JL, Duley L. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping and other strategies to influence placental transfusion at preterm birth on maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Sep 17;9(9):CD003248. link

- Duley L, Dorling J, Pushpa-Rajah A, et al. Randomised trial of cord clamping and initial stabilisation at very preterm birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal 2017. Ed Published Online. link

- Armstrong-Buisseret L, Powers K, Dorling J, et al. Randomised trial of cord clamping at very preterm birth: outcomes at 2 years. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2020;105:F292–F298. link

- Badurdeen S, Davis PG, Hooper SB, Donath S, Santomartino GA, Heng A, Zannino D, Hoq M, Omar F Kamlin C, Kane SC, Woodward A, Roberts CT, Polglase GR, Blank DA; Baby Directed Umbilical Cord Clamping (BabyDUCC) collaborative group. Physiologically based cord clamping for infants ≥32+0 weeks gestation: A randomised clinical trial and reference percentiles for heart rate and oxygen saturation for infants ≥35+0 weeks gestation. PLoS Med. 2022 Jun 23;19(6):e1004029. link

- Karen D. Fairchild, MD; Gina R. Petroni, PhD; Nikole E. Varhegyi, MS; Marya L. Strand, MD; Justin B. Josephsen, MD; Susan Niermeyer, MD; James S. Barry, MD; Jamie B. Warren, MD; Monica Rincon, MD; Jennifer L. Fang, MD; Sumesh P. Thomas, MBBS; Colm P. Travers, MD; Andrea F. Kane, MD; Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Bobbi J. Byrne, MD; Mark A. Underwood, MD; Francis R. Poulain, MD; Brenda H. Law, MD; Terri E. Gorman, MD; Tina A. Leone, MD; Dorothy I. Bulas, MD; Monica Epelman, MD; Beth M. Kline-Fath, MD; Christian A. Chisholm, MD; John Kattwinkel, MD; for the VentFirst Consortium; Ventilatory Assistance Before Umbilical Cord Clamping in Extremely Preterm Infants A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(5):e2411140. link

- Ronny Knol, Brouwer E, Vernooij ASN, et al. Clinical aspects of incorporating cord clamping into stabilisation of preterm infants Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal 2018 Sep;103(5):F493-F497. link

- Brouwer E, Knol R, Vernooij ASN, et al. Physiological-based cord clamping in preterm infants using a new purpose-built resuscitation table: a feasibility study Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal 2018. link

- Ronny Knol, Emma Brouwer et al. PBCC in very preterm infants, RCT on effectiveness of stabilisation. Resuscitation 147 (2020) 24-33. link

- Ronny Knol, Emma Brouwer et al. Physiological versus time-based cord clamping in very preterm infants (ABC3): a parallel-group, multicentre, randomised, controlled superiority trial. The Lancet Regional Health Europe Published December 4, 2024. link

Langegracht 70

2312 NV Leiden

The Netherlands